MARION BATAILLARD

NOTRE CORPS

7 SEPTEMBER — 21 OCTOBER 2023

PARIS-B is deligted to welcome Marion Bataillard for her first solo show in the gallery Notre corps, where she reveals her new group of paintings.

When she paints, Marion Bataillard seems to be seeking full awareness of herself and the world around her. The spaces she depicts act like jewel cases. — Henri Guette

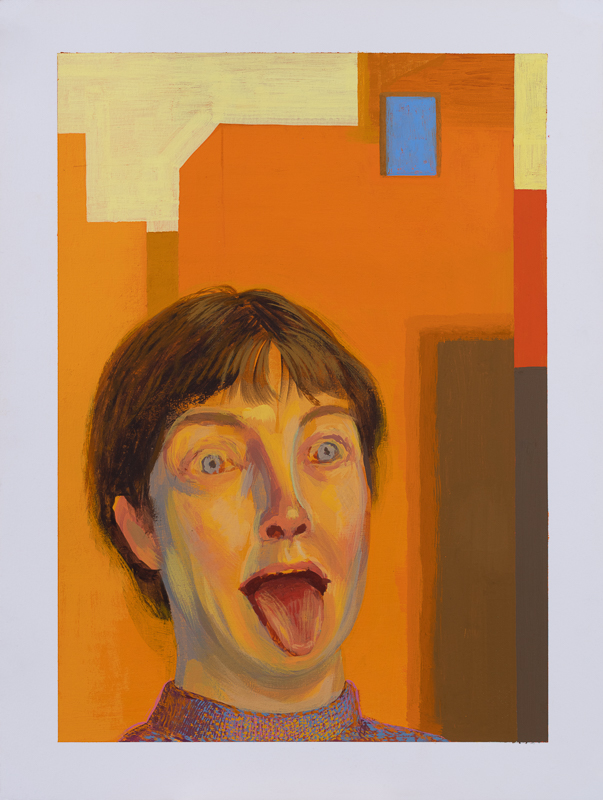

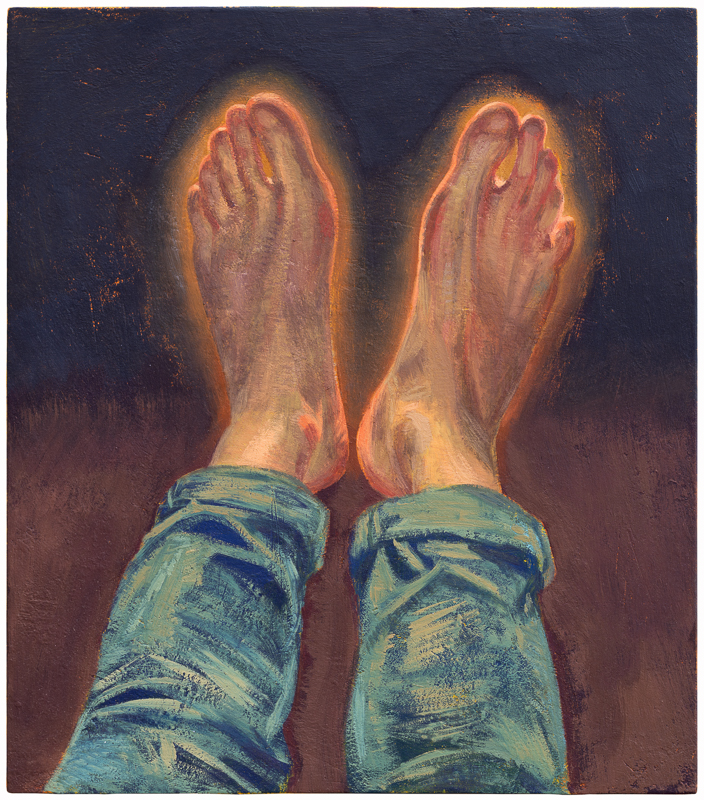

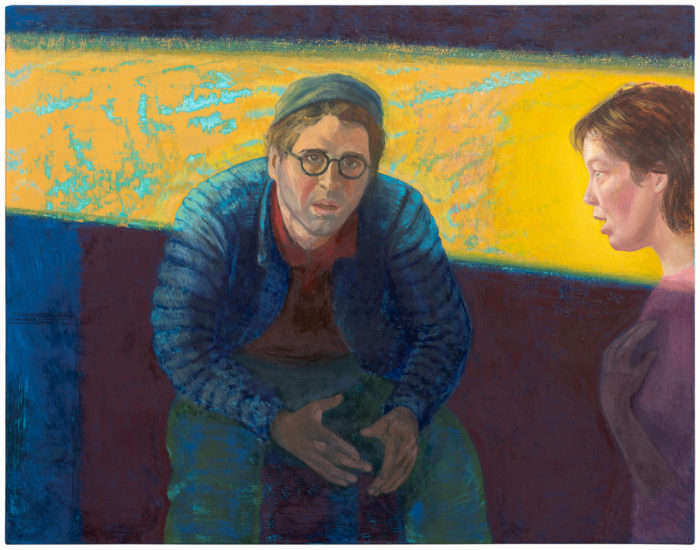

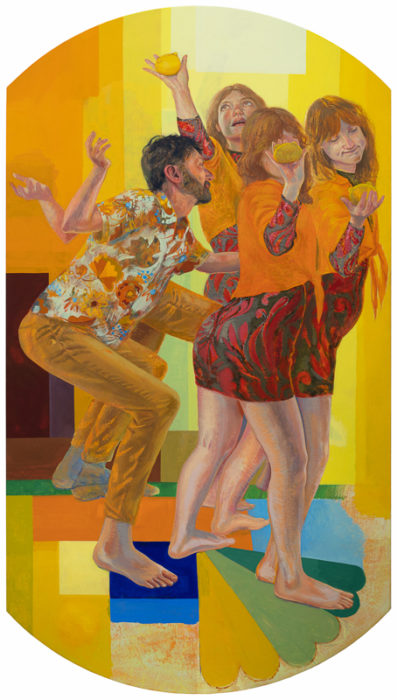

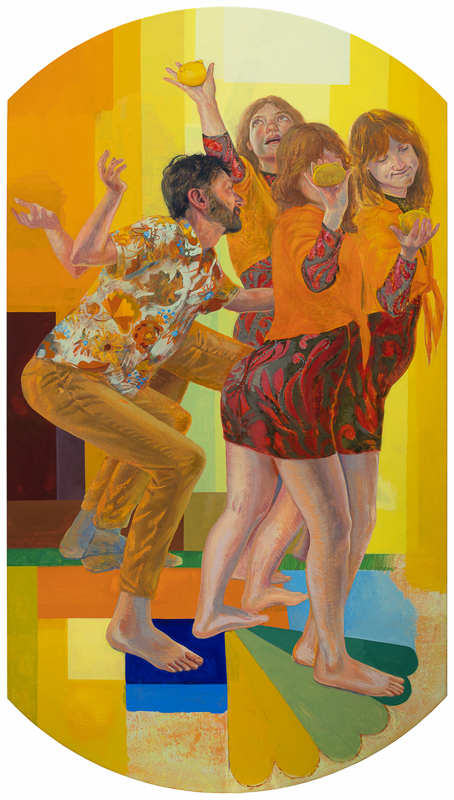

« In this new cycle of paintings, Marion Bataillard represents architecture and dance. Transfigured urbanity, expressive bodies, vibrant colors, the concrete framework of large cut-out panels… From the outset, their geometrics form a frame, serving as a counterpoint to the movements and expressions of the utterly human figures she shows. Because nature doesn’t make straight lines, the rectilinear brought in by man both balances and constrains the irreducible meandering of the body.

This is precisely what the deployment of spaces seems to emphasize: our bodies, affected in different ways. Marion Bataillard’s characters are intriguingly polysemous. Tinged with ordinariness and brimming with desire aching to be fulfilled, their attitudes hint at a symbolism requiring interpretation. Calm, smiling, or suffering, their countenances offer an unsettling presence that captures the gaze. Could it be that these faces are the real subjects of her paintings?

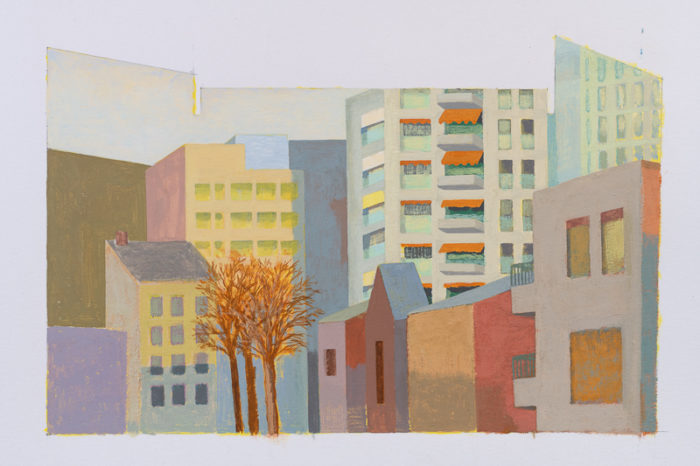

But in the centerpiece of this new exhibition, Place de la Réunion, the built environment is also based on another principle: the City, center of our existential situation. Illuminated by a sun-like hole in the central panel, the whole scene turns mystical. Somehow, it inaugurates an unprecedented sacred conversation between characters who yet seem familiar, allowing transcendence to emerge in the public square.

Extraits du film réalisé par Alain Della Negra sur Marion Batailard dans son atelier, 2023

Marion Bataillard is one of those painters who are reviving the methodological challenge of the classical painting, by prioritising the carnal, and therefore cognitive, relationship with the support, the format, the space and the bodies. — Roméo Agid

Through its raw and rudimentary treatment, architecture appears as an obvious symbol of our times, the default habitat of Homo sapiens where the lives of most of us now flow.

(…)

If Marion Bataillard is clearly concerned with situating her art in history, she is also engaged in a pictorial process that leaves room for the unknown and for experience. The idea is conditioned by a format, by the singularity of a model she invites to pose, or by the uncertainties of her current technique, tempera. Her material is increasingly pigmented, matte, and solid. The colors are bolder than ever, even becoming autonomous within their expanding fields, opened up by the singular shapes of the panels.

Surprisingly, a work like Travail de l’ombre summons the shaped canvases of American minimalist abstraction from the 1960s, while also connecting with the much older tradition of early Renaissance church painting when frescoes had to accommodate the constraints of architecture — before the art of representation, by now a portable commodity for bourgeois enjoyment, froze into the rectangular shape.

(…)

Within the paintings and from one canvas to another, we travel through seemingly disparate realities, mirroring the entangled chaos of life where everything appears disorderly, unexpectedly, or as the English expression goes, “everything everywhere all at once”. The thing’s felt, and we feel that too. »

Catalogue of Works

BIOGRAPHY

Marion Bataillard is a French painter born in 1983. She studied at the École Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs de Strasbourg under Manfred Sternjakob and Daniel Schlier, then at the Leipzig School of Art in Neo Rauch’s class; she lived in Berlin until 2013. In 2015, she received the Grand Prize of the 60th Salon de Montrouge. She now lives and works in Ardèche. In a few years, Marion Bataillard has risen to the forefront of young contemporary French painting.