Shao Bingfeng was born in 1947, in the village of East Putou, in Wen Deng city, Shan Dong Province. She had three brothers and one elder sister and three younger sisters.

Shao went to elementary school in 1955. Like most villagers at the beginning of New China, Shao’s family was extremely poor.

In 1958, Communist Party Chairman Mao launched the Great Leap Forward and established People’s Communes to force people in the countryside to collect steel.

In order to achieve the steel production targets set by local cadres, like most students and farmers in countryside, Shao’s life became an endless search for steel once the People’s Communes had collected all the steel products found in people’s homes.

In 1960, Shao graduated from school, right at the start of Great Chinese Famine. Food was in desperate shortage, which caused millions of deaths. Shao and her brothers and sisters survived by eating wild leaves from trees on the mountain.

In 1961, Shao was admitted to the second junior school of Wen Deng city while the three-year Great Chinese Famine was still going on. Shao only had sweet potato leaves to eat and her father’s old clothes to wear; it was the most difficult period in her memory.

In 1964, Shao failed out of high school and started to do farming. After two years of textile work with twine and sacks, Shao spent one year weaving baskets and another two years doing embroidery.

Soon, in 1966, China’s Cultural Revolution was on its way. It resulted in widespread factional struggles in all walks of life. And during the Revolution’s Down to the Countryside movement, young people like Shao living in villages were forced to work day and night by the local cadres in the spirit of collectivism.

In 1967, the Cultural Revolution began. She never got to work because of it. The whole country’s education was stopped. In Shao’s village, teachers suffered a wide range of abuses, including public humiliation, arbitrary imprisonment, torture etc. Her dream of going back to school was broken.

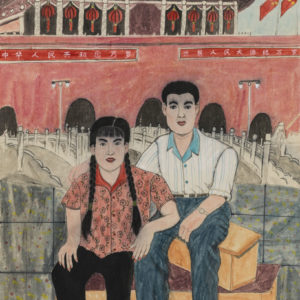

On the 1st of May, 1971, Shao married Bi Shufang, an oil worker at the 5-7 Oilfield. Shao’s eldest daughter was born in 1972 and soon, in 1975, she had another daughter.

Life was still tough for Shao, raising two kids alone in her husband’s homevillage when her husband had to be apart from them to work on the oilfield.

Shao was united with her husband in 1978. She moved in with her husband in Sheng Li Oilfield with their two daughters. Making a total of 52 Chinese Yuan each month on her husband’s salary, Shao’s family barely had enough food.

In 1980, Shao’s husband’s company arranged a job for her in their nursery, paying 25 Chinese Yuan per month; life was finally getting better.

From 1982 to 1989, Shao worked at the Zhong Yuan Oilfield, at a coal factory, a restaurant, and at the Zhong Yuan mud company for four years. In 1989, Shao started to work for the accounts office of the Zhong Yuan Oil field Newspaper, and stayed until she retired in 1995.

In 2002, the son of her eldest daughter was born. Like most of the modern families in China, Shao began to do long-term care of her grandson in her daughter’s home – Ri Zhao city in Shan Dong province.

In 2006, Shao’s son-in-law was admitted to the Nanjing Arts Institute as a masters student, so Shao and her grandson were invited to join them in the rental house of an island of Nanjing to spend the summer.

As usual, Shao read comics with her grandson and watched him draw dinosaurs, birds and other animals. One day Shao was really bored and saw a photograph of her grandson with her, which inspired her to draw the photo right away. This was the very beginning of Shao’s creations.

In addition to doing some housework and taking care of her grandson, Shao started to draw to kill time in the summer of 2006, after her work got encouragement from her daughter and son-in-law; now, unexpectedly, she has drawn more than 200 works in 8 years.

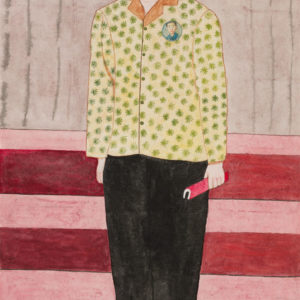

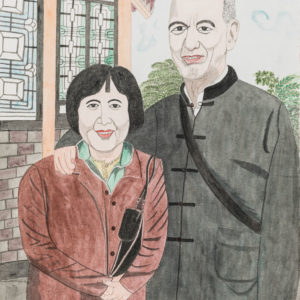

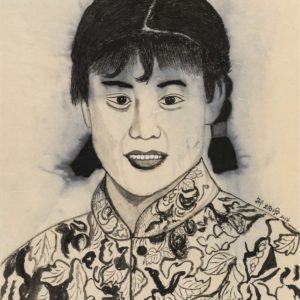

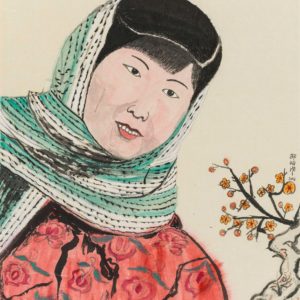

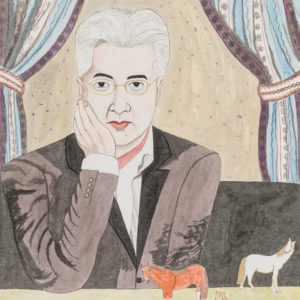

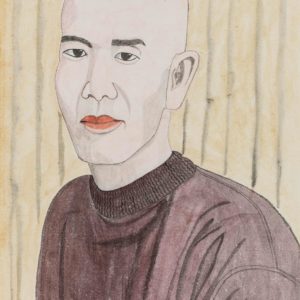

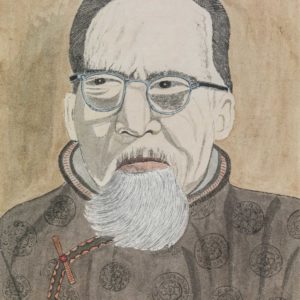

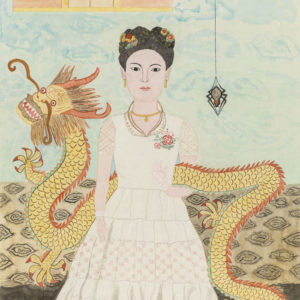

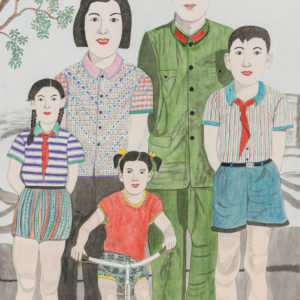

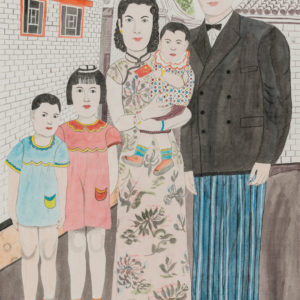

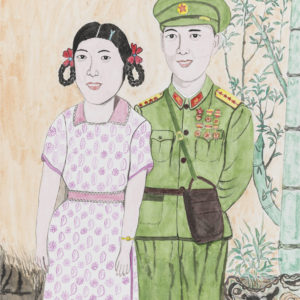

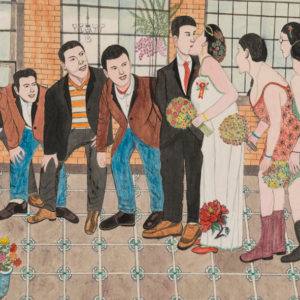

Shao’s drawings are a completely spontaneous creation. Her drawings unconsciously engage with the notion of identity within Chinese culture over half century, either the special period of the Cultural Revolution and collectivism, or the economic reforms of the country.

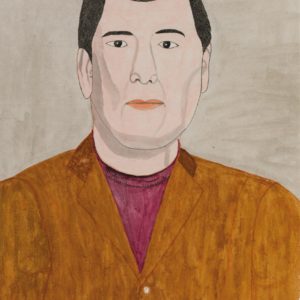

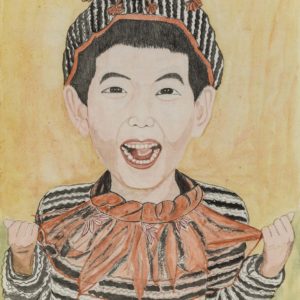

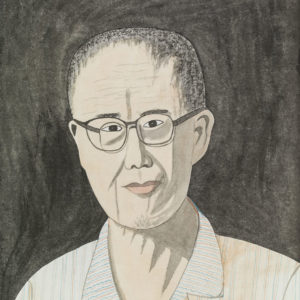

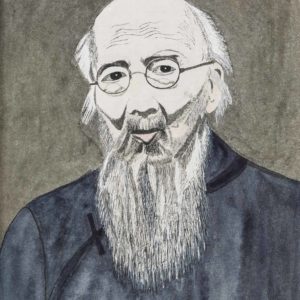

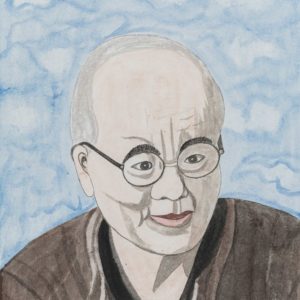

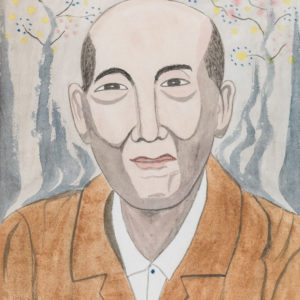

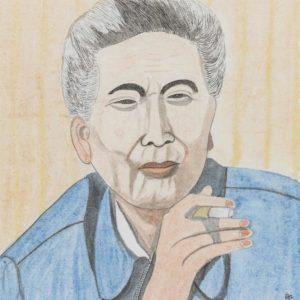

Shao never had any professional training or artistic habits, but followed her own mind and imagination to recreate from photos (many are black and white portraits) with colour and new structures.

Shao’s works depict a genealogy of her family: imaged documents of changes of the time, a historical background. The figures and composition of Shao’s works are mostly based on family photos. As readers, we can easily get the concept of family through her works – extended, societal, and the unneringly similar, distinguished by differences in content.

Shao does not simply copy photography in her drawings; in her creations she uses a unique language that keeps the rich mood and physical features of the photos while creating a sort of exaggeration of layers of animation and stoic flatness. Big bodies, small heads and subtle alterations in hairstyle give a complex dimension to her works, initiating suggestive narrative readings: a chronicle and evolution of the typical contemporary Chinese family. All Chinese people and the people who have experienced life in this country would easily be able to find strong emotional resonances.

-

SUMMER GROUP SHOW

07/01/2018 - 07/28/2018