Born in Hubei province, 1970.

Currently lives and works in Beijing.

SOLO EXHIBITIONS AND PERFORMANCES

2015

Vision, New Campaign for Pernod Ricard, Presented at Paris Photo, Grand Palais, Paris, France

Beyond Gravity, Galerie Richard, New-York, USA

2014

Fly over the Ringling museum of art, Florida, USA

Fly over Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Holland

Fly over Milan, Italy

Fly at The Grand Palace, Paris, France

Fly over the Ringling museum of art, USA, Florida, USA

Li Wei – High Place, Galerie PARIS-B, Brussels, Belgium

Li Wei – High Place, Galerie PARIS-B, Paris, France

2013

AUTOSTADT, Wolfsburg, Germany

Flying of Dreams, ZAT Montpellier, France

Anti Gravity, Shanghai

2012

Li Wei – Reality Anew, LDX Gallery, Hong Kong

Li Wei, Dock Sud Gallery, France

Li Wei, La Villette, Paris, France

The High Life of Li Wei, Kunst Llicht Photo Art Gallery, Shanghai

2011

Li Wei, Lucca Photo Fest, Lucca, Italy

2010

Beyond Gravity, 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong

Li Wei Performance – Take Away, Shanghai Tang, Hong Kong

2009

Li Wei” Galeria TRIBECA, Madrid, Spain

The Amazing Mirror Maze of the Self, Michael Schultz Gallery, Beijing

Besides Gravity, Mogadishni CPH gallery, Denmark

2008

Li Wei Exhibition, Yeh Rong Jia Culture & Art Foundation, Taiwan

2007

Li Wei Falls To…, Espace Cultural Ample Gallery, Spain

2006

Li Wei Exhibition, PYO Gallery, Seoul

Transcendence: A Mirror of China, New York

Li Wei Exhibition, 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong

Li Wei Exhibition, Grleria Espacio Minimo, Madrid, Spain

2005

Illusor Reality, Marella Gallery, Beijing

2004

Li Wei Exhibition, Marella Gallery, Italy

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2015

Heaven and Hell. From magic carpets to drones, Boghossian Foundation, Brussels, Belgium

2014

Photography and Video Art in China Now, The Ringling Museum of Art, USA

Itinerary, Gidang Museum, Korea

Liquid Times, Seoul Museum of Art

Bin He 1996-2004, Songzhuang Museum of Art, Beijing, China

Public performance Flying over Grand Palais, Art Paris Art Fair, Galerie Paris-Beijing, France

2013

The 55th Venice Biennale, Venice Biennale Kenya Pavilion, Italy

Norev-Over, collective photography and video exhibition, Beijing

The Rapture of Romantic Illusions, Fudi Aromatic Villa, Shanghai

IncarnatIons Photographie-Performan de Chine, France, Angers

The change – the second Hunan young artists nominated Exhibition Changsha, China

See But Not Now, Shanghai, China

Roots Of Relations Songzhuang Art Center, Beijing, China

2013 Rapid Pulse International Performance Art Festival, France

2012

A History of Chinese Contemporary Photography, Galerie PARIS-B, Brussels, Belgium

Incarnations, Galerie Paris-Beijing, Paris, France

Contemporary Chinese Photography, Katonah Museum of Art, USA

Now! China! Korea! 2012! – Contemporary Korean and Chinese Art Exhibition”, Gallery TN, Beijing

Standing At The Water’s Edge, M97 Gallery, Shanghai

Dream City Tunisia 2012, Tunis

Daydreaming With…, Hong Kong

Research Exhibition On ‘Post-70s Generation’Artists Jianghan Star Plan 2012 Rejoice In Dissensus, Wuhang Art Museum

Monzza Shunde Biennale, Italy

L’Art De La Radiance-30th Anniversary Celebration Presented By Cle De Peau Beaute, Hong Kong

2011

Lucca Photo Fest, Lucca, Italy

I believe that… Chinese Contemporary Art exhibition, Songzhuang Museum, Beijing

Divided by The Curtains, Beijing Times Art Museum, Beijing

Chinese Visual Festival 2011-Lost In Transformation, London

Li Wei & aleiandro miranda, Galerie Daniel Tanner Gmbh, Zurich, Switaerland

St.Moritz masters, St.Moritz, Switaerland

box(e), Jerome Zodo Contemporary, Milan, Italy

Remaking Vision, Travelling Exhibition of Chinese Contemporary Photography

2010

Daegu Photo Biennale 2010, Daegu, Korea

Passing China, Gallery Sanstorium, Istanbul, Turkey

FUCK UPS, FABLES AND FIASCOS, Galerie Caprice Horn, Berlin

Foundation Vevey, ville d’images, Festival Images, Switzerland

CHINA PHOTOGRAPHS MADRID, Madrid Pavilion of the EXPO 2010, Shanghai

Mostra SESC de Artes 2010, St.Paul, Brazil

China Welcomes You Begegnungen 2010, Stadtmuseum Oldenburg

Photo Phnom Penh, Cambodia

2009

Beijing Time, Madrid, Spain

China: the Contemporary rebirth, Palazzo Reale Museum, Italy

Mouvement d’Art Public/Make Art Public (MAP), Canada

China Now: The Edge of Desire, Maxlang and Lillian Heidenberg Fine Art Presents, USA

Action-Camera: Beijing Performance Photography, Morris and helen Belkin Art Gallery, Vancouver

Incarnations, Galerie Paris-Beijing, Beijing

2008

Drawn in the Clouds: Contemporary Asian Art, Museum of Contemporary Art KIASMA, Helsinki

Fabricating Images from History, Chinablue Gallery, Beijing

Consumption of history, East Asia Contemporary, Shanghai

Out of place, Robischon Gallery, Denver

Beijing 2008, Olympic Museum, Lausanne

BODY ART: New photography from China, Asian Art Coordinating Council, Denver

2007

RED HOT – Asian Art Today from the Chaney Family Collection”, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Li Wei Weihong Huangyan, BarbaraDavis gallery, Houston

Floating”-New Generation of Art in China, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea

Made in China-China art Now, Louisiana Museum, Danmark

Chinese Photography, Criterion Gallery, Australia

Dragon’s Evolution, New York China-Square Art Center,

SURGE, Beijing 798

The 7th Gana Photo Festival -CHINA contemporary Photo & Vide, Gana art Center, Seoul

Szene-sommer’07, Salzburg Art Center, Austria. Zhuyi, Artium Museum, Spain

CHina Now: Lost in Transition, Eli Klein Gallery, New York

SURREALITES, CentrePasquArt Art Center, Switzerland

2006

China-Between Past and Future, Performances Art-Haus der kulturen der Welt/House of World Cultures, Berlin

RUINS, USA

COLD ENERGY, PYO, Beijing

Park in progress, France

For All Audiences, SALA Rekalde Art museum, BILBAO, SPAIN

Retours de Chine, Toulouse Art museum, France

2005

THE SECOND REALITY Photographs from China, “Piazza” of the Berlaymont building, European Commission

THE GESTURE-A VISUAL LIBRARY IN PROGRESS, Macedonian Museum Of Contemporary Art, Thessaloniki, Greece

New Photographers 2006, Gettyimages, Cannes

BFF-KONGRESS HAMBURG 2005, HAMBURG

Ruins`Flowers, OX WAREHOUSE, Macau

Out Of the Red-2, Marella Gallery, Italy

70 empress arts, Shanghai

2004

Between Past and Future- New Photography and Video from China, ICP, AsiaSociety, New York. Smart Museum of Art, Chicago

Officina Asia, Bologna, Galleriad’arte moderna Cesena, Italy

TIANANMEN Exhibition, Paris, France

MMAC Exhibition, Japan

Artificial merriment, Melbourne, Australia

FOLLIA Exhibition, Italy

2003

China Art Now — Out Of the Red, FlashArt Museum, Italy

I am China– Chinese Conceptual Photography, SOHO, Beijing

Manufactured Happiness Shangri-La Art Space, Beijing

The peripheries become the center, Prague Biennial

DNA Visual, Beijing

Bare Androgyny, Beijing

Seoul-Asia Art Now Exhibition, Seoul

2002

Flying – Performance, Photography, Video, Beijing Red Square, Beijing

The 2nd ‘PingYao’ International Photography, PingYao, Shan Xi, China

Red Square – Contemporary Art” Exhibition, Beijing Red Square, Beijing

Mask Vs Face, Red Gate Gallery, Beijing

Bogus – Chinese Conceptual Photography Exhibition, Hall of Capital Normal University, Beijing

MOIS DE LA PHOTO –HISTOIRES de CHINE, Auxerre, France

2001

0.C Art Exhibition, Beijing Bridge Art, Beijing

Constructed Reality–Beijing/Hong Kong Conceptual Photography, Hong Kong Arts Center, Hong Kong

Pawn. COM –Site Performance, Happy Garden Bar, Beijing

Scar–Chinese Conceptual Photography, Exhibition Hall of Capital Normal University, Beijing

Site of City — Four Person Conceptual Photography, Fun Gallery, Beijing

AWARDS

2005

Macau Art museum overseas communicate the prize-Macau art museum

2006

31 photographers with the most creative world-American Getty

-

LI WEI

HIGH PLACE

11/08/2014 - 01/10/2015 -

LI WEI

HIGH PLACE

03/13/2014 - 04/26/2014

LI WEI TALKS ABOUT HIS WORK FOR THE CREATOR PROJECT

High Place

Press Release

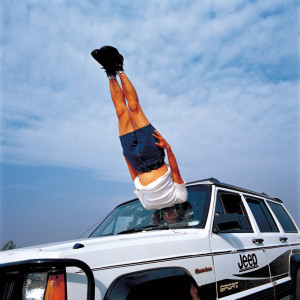

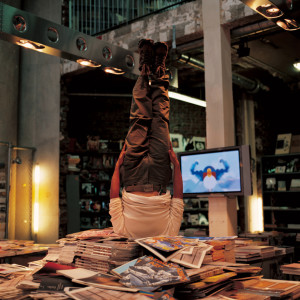

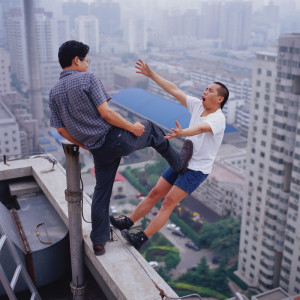

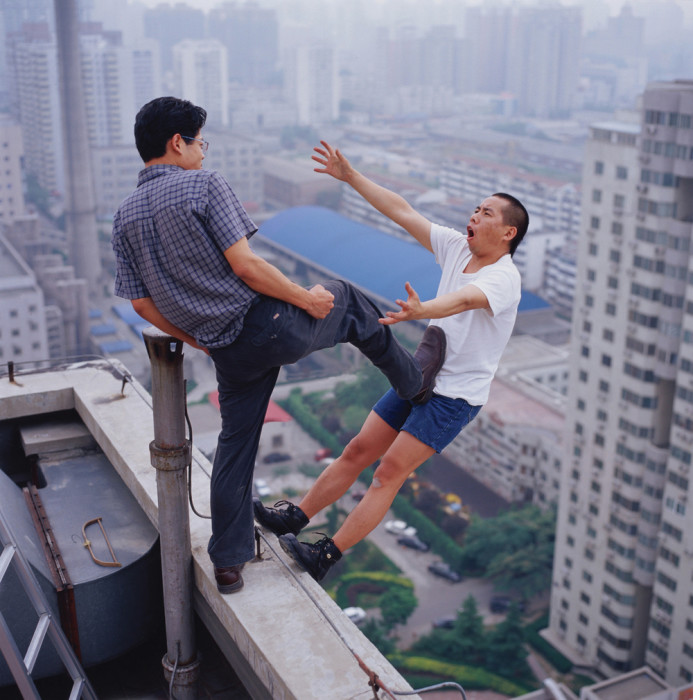

Internationally known for his amazing photo-performances, Li Wei stages his body in contemporary landscapes and creates the illusion of gravity-defying situations that are dangerous and humorous at the same time.

Floating in the air, on the top of a skyscraper, or falling upside down from the sky, with his head embedded into the ground, the Chinese artist doesn’t uses computer montages, but mobilise cranes, scaffoldings and metal wires to achieve his acrobatic images.

Li Wei’s art is a difficult process mixing acrobatics and photography. His work questions our perceptions of social spaces and expresses a need of freedom: it draws out the fine line between reality and fantasy and points it out to the audience.

For this exhibition, Galerie Paris-Beijing shows a large selection of photo-performances Li Wei has staged between 2003 and 2013, in China and worldwide.

Li Wei was born in 1970 in the Hubei province and moved to Beijing in 1993, where he actually lives. In 1996, he met the avant-gardist group of the Beijing East Village, such as Zhu Ming and Zhang Huan, and began performing in the public space.

Li Wei’s artwork has been exhibited in Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America. The most recent group and solo exhibitions include Venice Biennale (2013), Parc de la Villette, Paris (2012) and Rencontres d’Arles (2007).

Li Wei’s Body of Art

by Julie Segraves

(Asian Art Coordinating Council)

The focus of cutting edge art in China today has shifted from sculpture and painting to performance, photographic and video art. Many forward-thinking artists now use the human body as their canvas and in the process, are creating conceptual art, which is then captured, and even heightened by photography and video. Some of the first examples of conceptual or idea- based photos, documenting underground performance art, were taken during the mid 1990’s at the East Village, an art community located to the northeast of Beijing. At the end of the 1990’s some photo artists were also working with digitally enhanced computer images. Subsequently, by the early 2000s conceptual photography had evolved into a well-established art form. Today some of the most distinctive work is the matchless mixture of performance art and photography being created by the artist Li Wei.

This Chinese Evil Knievel uses his own body to produce works that are both unsettling and provocative and, at times, comic in their deadpan delivery. What Li Wei does not present is the traditional imagery of past party leaders and the pageantry of their political programs. Instead, the social context of Li Wei’s work reflects his unease with China’s globalization and the constantly changing urban environment, coupled with the more personal concerns such as love, family, happiness, and disappointment.

Born in 1970 into a Hubei province farming family, few of his fellow villagers could have imaged that Li Wei would someday become a well-known artist. At age 19, like millions of other young people, Li Wei migrated to Beijing in pursuit of fame and fortune. Lacking the academic qualifications to be admitted into the prestigious government- run Central Academy of Art, in 1993 Li Wei enrolled at the privately- run Oriental Arts College, where he studied painting. But being interested in contemporary painting, Li Wei soon realized that he was learning little from his traditionally- trained art teachers and dropped out after one year. In order to survive Li Wei worked at a variety of low paying jobs, but soon recognized that regardless of much as he worked, there was never the money or time left to pursue his own art. After befriending independent artists living in the East Village, Li Wei quit his dead-end jobs and radically changed his artistic direction. First, he taught himself photography and video, and then in 1997 Li Wei began to pursue performance art as his primary artistic medium. For Li Wei this distinctive and inspiring art form was ideal. It enabled Li Wei to have a dialogue with his audience and to bring them into the artistic process. In addition, performance art also allowed Li Wei to create and manipulate his own fantasy realities.

Li Wei began to use mirrors in a distinctive way to scrutinize and play with reality. Patrons at the Shanghai 2000 Biennale witnessed one of these first public performance art pieces, Mirroring. In this, and the many performances in the series that followed, Li Wei is featured wearing a 3-foot wide mirror with his head emerging from a hole in its center. The Mirroring pieces, documented by photos, reflect Li Wei’ s head floating among his viewers in everyday living spaces, in various urban settings, and at well-known historical sites. For Li Wei these disconcerting interactive performance pieces punctuate the tension between the real and the unreal. They cause, as Li Wei says, ” To question our everyday habits of perception. We see ourselves and our surroundings from a new point of view.”

Combining acrobatics skills with wires and scaffolding, Li Wei began what is probably one of his best-known series to date, Falls, in 2002. These pieces are anything but easy to execute. In Li Wei Falls from the Sky, the artist is shown with his head and chest embedded in the blacktop of a country road. His absolutely rigid legs pointing up to the sky resemble a human rocket that has just crashed into the earth. These art not computer montages images, only the wires and scaffolding that keep Li Wei’s body erect have been cropped out of the photos. Commenting on China’s fast changing and unfamiliar society today, Li Wei states, “If you picture someone falling to earth from another planet, there would really be no soft landing, whether the landing were in China or in another part of the world. This feeling of having fallen headfirst into the unknown and of having nothing firm under one’s feet is familiar to everyone. One doesn’t have to actually fall from another planet to feel that way.”

Featured in the 2003 Free Degree Over 29th Story performance piece, superman-like Li Wei appears to defy gravity by flying out of a window. Will he eventually miraculously take to the air among the multi- stories structures of Beijing’s Central Business District, or quickly crash into the earth? For Li Wei this work represents the feelings of many Beijing office workers, who would like to escape from their dreary jobs, but can’t since their work is essential for personal survival as well as for the continued expansion of China’s economy.

However, even dare- devil Li Wei had reservations about the execution of Free Degree:” I was in fact dangling from the 29th floor of Beijing office complex and needed really large, muscular people to hold onto my ankles. There are not many large, muscular people in Beijing. But finally I did find several, and fortunately for me, it all worked out and I am still here.”

Li Wei’s gymnastic ability is put to the test again in Life is High, a three-piece photo series created in 2004. This triptych features a hair-raising performance in which a female companion holds onto one of Li Wei’s ankles then throws his body through space like an Olympic shot putter. For the artist this amusing piece explores the universal problem of contemporary male-female relationships. Although every relationship has its tender moments, reflected in the middle photo, much of a couple’s time is spent dealing with the actions, reactions, and expectations of their partner. As these photos clearly show, women are not only the stronger sex, but also seem more frustrated than their male companions.

The surreal scene featured in A Pause for Humanity (2005) is Li Wei’s artistic statement about preserving the family in the face of a swiftly changing China. The piece presents the artist holding his baby while dangling precariously within a series of steel girders. It appears that father and child will soon plunge to their deaths, and their faces reflect their anxiety. Li Wei believes that within China’s quickly shifting society many people feel that are they are losing their grip, and that they cannot afford to take anything for granted: “It’s a feeling of hanging in the air. And even if family is our priority, we wonder just how much we are really able to do.”

In another triptych, Ahead (2006), a suited Hong Kong businessman stands inside a white BMW convertible which is parked in front of Hong Kong’s harborscape, all emblems of financial success. With one hand he tosses the body of an unsuspecting Li Wei forward like football, while his other hand points to an unknown future. Although citizens are urged by government officials to become consumers and to help modernize and globalize China, the at first stunned, then skeptical, and finally sacred looks on Li Wei’s face in the three consecutive photos reveal his ambivalence about the social outcome of these future economic possibilities.

In 2007 while walking through Beijing’s 798 Art District Li Wei happened to see a large plastic arm emerging from the upper story of a building; the arm was part an art installation. Li Wei then used the same arm in his own creative piece, Illusory Reality. In this work Li Wei demonstrates his insight into the psychological state of the Chinese people during this time of unprecedented social transition. Most Chinese citizens are experiencing individual freedom unheard of since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in1949. But at the back of their minds they also know that the long, and ever- present arm of the Chinese government can sweep in any at any moment, changing their destiny, resulting in a whiplash of anxiety.

In contrast, another 2007 photo, Never Say failure, features a team of Chinese basketball players appearing to resist gravity’s reality. With the help of cables photo-shopped out, they fly through the air with the greatest of ease, slam dunking Li Wei’s body into a basketball hoop. This photo is Li Wei’s artistic assertion that even against impossible odds, where there is a will, there is always a way.

In a recent 2008 photo, Life at the High Place # 5, Li Wei explores the current Chinese preoccupation with the purist of prosperity .The piece presents an apprehensive Li Wei awkwardly holding onto the steering wheel of a white BMW convertible, while piloting the flying car over the rooftops of Beijing. Barely hanging on, but coming along for the ride, are a group of his friends. Each friend precariously holds onto the ankles of the previous person, creating a virtual trail of people in the sky, all dutifully pursuing wealth and luxury.

Li Wei’s compelling but provocative performance art pieces continue to ingeniously explore the multiple realities of China’s complex contemporary society within the staged fantasies that he creates. Some of his photos are indeed humorous, while others are disconcerting, but all provide fascinating insights into both the artist himself and into China today.

Towards the Infinite Space

On Li Wei’s Performance Photography

By Wang Chunchen, September 8th, 2008

(China Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing)

Li Wei is one of the most influential contemporary artists of China and he has focused on his idiosyncratic performance since 1999. He then becomes increasingly noticed by the international community of art. How and why Li Wei has achieved such a reputation and recognition is an interesting topic for discussion. The past twenty years have seen great changes in China’s society and Chinese psychology on their environments. On the one hand, China is never the same country as compared to its history and to its former social structure. Many a buildings and high roads are built across China, the traditional and conventional life and habits are challenged and uprooted, although it becomes more convenient to access to those remote areas, a great number of heritages are destroyed and disappeared forever from the sight. Therefore, on the other hand, the sensitive people feel strongly displaced and discontented; especially the new generation of Chinese conceptual artists find their own ways to reflect such vicissitudes and transformations. When we look at the art created by Chinese artists today, we need to make discrimination of it. For different artists have different understanding of what contemporary art is or should be, the results of what they make are quite variant and contradictory in methods and conceptions. As for the true contemporary art criticism, only those works made by some who feel irrepressible impulse and reactions to contemporary life and society are of interest to us. Therefore, when Li Wei made his first performance with mirror holding in arms, he created some unique icons of contemporary conceptions. The general audience and art critics are surprised by this double image reflected through the mirror and camera lens. Following this particular representation of reality, Li Wei creates another icons of interpretation of life and desire: he usually uses a thin steel wire to be tied on his ankles to hold himself up or catch himself not falling down from the air. Because of the absolute challenge of the gravity, Li Wei’s suspending performance becomes a symbol of contemporary life, both referring to the physical limits and to the psychological adjustment. The backgrounds he sets himself in are those remains of the past life experienced by Chinese people, such as Forbidden City, building roof, turned-down house relics, some abandoned factory, construction site, rural field, and etc. All such places are closely linked to Chinese life and China’s reality, from history to present moment, from social changes to personal aspirations. Li Wei’s methods of representative icons are then considered as some contestation of reality and virtuality. What he creates is just the ubiquitous sentimentality of contemporary people showing to their outside world – they are controlled by some power but couldn’t escape away. However, they still like to make efforts to break loose, aiming at the pursuit of absolute freedom and re-creating of our senses of the outside world. Li Wei seems look like an actor to test the limits of physical capacity in the real life, to confront the cognitive habits for human actions and their concepts – it is impossible for us to act in such ways. In fact, such efforts as performance or as the product of conceptual photography are direct embodiment of today’s Chinese artists’ conception of how to make art. Since 1990s and after the 21th century, avant-garde Chinese artists have tried their best to break through all the restrictions defined upon art, especially in China’s situation, making art means potential ideological connotations and subtexts. One of such restrictions is that the individual expressions of artists might be retained under the slogan of the so-called mainstream voices – official advocacy of that art should be used to serve some socialist politics. But more and more avant-garde Chinese choose to do their own experiments on art making and art expression. So Li Wei came to the front with his special methods of breaking through the officially-supported realism, the audience could feel a strong surprise and curiosity that art could be done in such ways that brought marvelous experiences around their living reality and their senses of physical world. Firstly, performance has been a kind of taboo for official explanation of what art is: the later is always apt to consider performances as some gaudy acts or as superficial tactics. But in actuality, performance has intense impact upon people’s mind of conceptions, and gives rise to the collapse of stereotypes of art definition. This is why when Li Wei jumps into the sea or flings himself outwards through the windows or on the ceiling, people feel unexpectedly shocked and silenced: they get indistinctive and fresh experience which means more possibilities of reorganizing the world around us. This is done by our body – which as an everlasting field of conceptual embodiment – to act against the normality of our senses but towards the infinite space of multiple representations of the art structure.

Places I choose are suitable for my purpose of works.

Lost Gravity

The Photographs and Performances of Li Wei

by Ellen Pearlman, November 2006

Li Wei, a short and stocky man, clambered up a metal ladder ten feet, sticking his head deep into a hole in the wall. Two somber assistants using wire pulleys clipped mountaineering carabiners to his waist and feet, causing him to dangle horizontally, his hovering body a metaphor for pre-Olympic China-headless, suspended, and hurtling towards an unknown future.

A few days later I sat down to talk to Wei. He had just completed one of his signature jettisoning his body through space performances atop the roof of a building on Canal Street, appearing to dangle weightless across the downtown skyline. Our conversation was translated by Zhang Zhaohui, a curator and critic who is working on opening the first museum of contemporary art (MOCA) in Beijing. Wei, nursing a bleeding gash on his forearm, turned down medical treatment to answer my questions.

Why, I asked, had he been hanging horizontally from the ceiling the previous evening? What did it have to do with contemporary China, or for that matter, with New York? Filling me in on some historical detail, he explained that since 2003 the official Chinese government attitude towards performance art has relaxed, especially as officials seek more international cachet and recognition. Originally trained as a painter, Wei has produced an unsettling series of self-portraits involving his face reflected in mirrors in public places, and photographs of himself crashing into walls and sidewalks, many of which are included in the exhibition. He also has a number of photos where he seems to free fall from tall buildings-pictures that resemble the famous photograph of the French artist Yves Kline hurtling out a window. He creates these hair-raising performances to convey his continual sense of lost gravity, resulting from China’s hypersteroid pace of opening to the outside world. The new China is coming face to face with globalization, differing economic systems and shifting political landscapes. The identity of the good Communist comrade of the past has evaporated, producing a whiplash of anxiety. A new class struggle is re-emerging between the rural poor and the big city nouveau riche. Ethnic minorities like the Uyghur Muslims are reasserting their cultural identities while North Korea is detonating nuclear weapons on China’s doorstep. The environment is continually being degraded. The most immediate, visceral response to all of this for young artists is live action and performance art coupled with images from technology and 3-D gaming. Performance directly bypasses centuries of traditional painting and sculpture to deliver extremely modern imagery (though Wei felt that in the 1960s and 1970s contemporary art was linked more closely to text).

In the 1980s the first performance art trickled into China. works_ by Christo inspired a frenzy of ersatz Great Wall of China wrappings. But artists have moved beyond these first clumsy attempts and are now grappling with their responsibility to provide a new type of art. However, having jumped over the chasm of propagandistic Social Realism, landing directly into the jaws of postmodernism, many artists are debating whether this breakneck pace is too fast. They wonder if they are producing pieces that are just a mimicry of the west.

So, in a roundabout way, this is the reason why Li Wei stuck his head into the wall in a gallery on Canal Street. It is also the reason he continues to stick his head into obstructing surfaces or fragmented mirrors, and appears to fly/fall/float out from buildings and rooftops. He is the new China lost, a China without gravity.

Transcendental Experience

by Zhang Zhaohui, December 2005

A man falls to the ground from the air, his head cuts into the earth like an unexploded bomb. This astonishing image made by young Chinese artist Li Wei, entitled Li Wei Falls To Earth (2002), featured on a cover of an issue Flash Art in 2003.Over the past four years, works_ by the Beijing-based artist have been featured on the covers of a number of prestigious journals. Why has Li ’s art drawn such interest and attentions?

His first significant public exposure was at the Tbird Shanghai Biennale in 2000.During the opening ceremony, without any official invitation, he entered the gallery lobby to execute a performance piece. He showed up with a three -foot -square mirror with a hole, large enough to accommodate his head and neck. He places his head through the hole, his face reflected in the mirror. Looking at the mirror, his face seemed to be floating with the audience opposite, also reflected in the mirror. Viewers were surprised to find their images overlapping with the artist’s face. This highly interactive and sensational work attracted a lot of photographers immediately, creating some in disorder among the viewers. Security staffs soon detained him and the police questioned him for half-an-hour. He told the police that he was merely doing his performance work, which was also accessible on the Internet. The police warned him not to do this in the gallery for security reasons. The performance, somewhat akin to a 1960s happening, was widely distributed through the Internet and other media. even though many photographers and editors were unaware of the artist’s name. Simultaneously, a provocative group show entitled Fuck Off, featuring the work of 30 artists, was opened, This show includes such shocking work as Eating A Baby, which predicted the nation-wide 2001 debate on performance art.

Li Wei, born in 1973 into a farmer’s family in Hubei province, moved to Beijing in 1993. he enrolled in a private art school to study oil painting but left the school after a year due to his disappointment with its dogmatic teaching methods. With the dream of being an artist firmly fixed in his mind Li made a great effort to survive in expensive Beijing. He worked at various jobs, including painter, designer, delivering good and food, and as a housekeeper. In his spare time, he made abstract style paintings. During this time he was the same as any of the millions of migrant workers, swarming into Beijing from the countryside to seek a better life. He once told me that his early experiences as a jobless person were crucial to his later artistic vision, since he had shares the hardships, anxiety, and depression of millions of ordinary Chinese.

Through his association with performance artist Zhu Ming, who were then a close friend to the East Village artists group, led by Zhang Huan, Li Wei was introduced to performance art, which, for him, at first sight, appeared both novel and inspiring. Li came to realize that performance art was a more effective way through which to execute his artistic concept, and that the human body was a more effective medium through which to carry out his artistic ideas. In the East Village art community, the shocking performance works_ by Zhang Huan and Ma Liuming opened his eye. Li came to understand the repetitive rhetoric of painting and decided to give up painting to engage with performance art.

As a young man moving to Beijing, Li Wei shared the experience of the remarkable social changes of the day with his contemporary. His work’s social context showed a concern with the urban environment, a word in which happiness, work, love affairs, hope, adventure, and disappointment occurred for him and his contemporaries.

At the end of 2000, Li wei showed me his works_, I was impressed by his unique creativity and immediately realized his potential as an artist. Over the past few years, we have worked together on many exhibition projects, including 0°C Project, Mask vs. Face, New Urbanism, and what a Wonderful Life. His works_ is always the most eye-catching. But three early works_ are particularly notable: It Would Not Die Away As Such(1999), Green Guy·Flag(1999) , and Transparent Ecology (2001) which predicts his later work.

It Would Not Die Away Such was a performance about an unrealized desire and the spirit of continuing life. Li lies on a bed in a dark farmhouse. His body and head covered by a pile of dirt, turning the bed into a tomb. But his penis remains erect for some 20 minutes’ until its strength fades. This piece lasted for about 30 minutes and was executed in an unremarkable farmhouse on the outskirt of Beijing, It was open only to a small group of artists and journalists who were worried about police intervene. Through humor and his weird performance Li wanted to express a lofty idea, a kind of unrealized life of equality, freedom, and democracy, something numerous educated Chinese people have dreamt of for a more than a century. In this piece Li looked at a future life through a dead man’s reality. The embarrassing image of a cadaver with an erect penis becomes an ironic symbol of a sublime thought and profound religious concepts。

The subsequent piece, Green Gay·Flag, took place in a farmer’s courtyard outside Beijing. A seven-meter pole, with a red flag on the top, was installed in the yard. With his body Painted completely with green pigment, Li climbed to the top section of the pole while making several sentimental postures with the red flag. His agile and masculine green body becomes more eye-catching within the setting off of the chilly winter weather. His body resisted both the coldness and gravity. No doubt the red flag reminds viewers of the Chinese communist revolutionary history 30 years ago, sharp contrary to the otherworldly, naked, green man. Growing up underneath the red flag was a popular saying during the 1950s and 1960s. With the collapse of communist ideology caused by the market reform and the opening up to the West, many Chinese lost their directions, experiencing difficult times as they struggled to get used to the new urban reality. Li Wei’s work comments on people’s response to the drastic ideological changes in China over the past two decades.

Transparent Ecology was presented on October 27, 2001, at Bridge Art Center, on the occasion of the opening of 0°C Degree Project. Li dug a pit in the ground, big enough to contain his body. He remains in the pit, with a huge mirror covering his body and showing only his head through a hole in it. His head through the mirror was inside a glass ball, along with a red rose and a bird on his bare head .Li moved the rose from time to time with his mouth to clear the steamed-up surface of the glass so that the bird and Li could see out. The performance, which also had the audience blow cigarette smoke into the ball through a transparent tube, lasted about three and a half hours, even heavy rain did not prevent Li from finishing the performance.

Mirror and glass gradually became the key media of Li’s performance art, his initial use of glass at the on-site performance, entitled Human Beings – Floating Substance, took place, at Happy Garden Club in 2001. Fragmented glass paved the stage. Li Wei slowly made his way onto the stage barefoot, his body covered with slivers of mirror, like an alien coming down the earth from the heavens. He moved slowly along a fluorescent rope, making it appear to pass through his chest, seemingly charging and sustains his body and movement. It took about ten minutes for him to finish the short walk. His debris-covered body sparkled with light from time to time, aided by the revolving light in the disco bar. The enthusiastic respond from the viewer encouraged him to performance more.

Over five years, the Mirror series performance has been performance at numerous historical and ordinary venues and in many contexts, Li usually performance his piece within such urban surroundings as Beijing’s newly built skyscrapers, highways, supermarket, highways, and supermarket, parks, and square. One significant performance of his piece took place in the late Autumn of 2003 Jianwai soho, a grand real estate project designed by Japanese architect Riken Yamamoto, in the Central Business District (CBD) of Beijing. The opening gala in this surreal-looking minimalist, white compound presented performance art as part of the programs, When his mirror-with-head was exposed to the crowd, Li Wei suddenly became the focus of the whole event, Inspired by the public exposure gained from this, Li quickly completed two news series-Free Degree over 29th Floor (2003) and Dream-Likes Love(2003)-—for the CBD’s brand new office building environment.

In his new work staged in the CBD, entitled Flying out of Window, Li exits from window of a glass-covered skyscraper like a flying bird, He is suspended over the void and ready to travel over our heads like Superman or our modern-day Icarus, and others are about to follow him out. This work expresses a desire of get rid of the tedious of daily office work that has been at the heart of the expansion of China’s economy and foreign investment in China.

Li Wei’s Dream-LikeLove series is a comment on the love game among China’s urban youth who have come of age in the new millennium. He utilizes illusion and reflection made through a mirror. Here, his head seems to have been cut off, to float in the air like a ball. A young girl has fun playing with it, holding his face into a sofa. The face functions as a lovely pet. This is like a double vision, a reflection of the current social surrounding for young people’s love life, The statement is that love is a wholly mental sentiment and that while a girl may love a man’s heart and soul (head), pure love is utopia since Chinese girls tends to marry rich men (body) who can maintain their high-level of material life, thus the artist’s head is only her soul-mate. This reflects the dilemma for young people when they are considering love and marriage. The candidate is either a poor man but spiritually desired, or a rich man but an upstart.

It is hardly to find another artist in China, or in the world perhaps, who uses the mirror better as an implement in his art than Li Wei. The most important contribution of the mirror to Li Wei’s work is that it provides an intersection between reality and its concealment, which is perceptively integrated. The in combination of the two not only presents us with an eerie pictorial world but also suggests metaphorically a feeling of alienation in uncertain world.

Another clear characteristic in Li’s work is the separation of the head from the body as emphasized byhis use of mirrors, sometimes what is visible is his head, as in Mirror Series, Translucent Ecosystem, and Simulation of Love, sometimes his body without its head is visible, as in Li Wei Falls Down series, To Save the Baby, and Walk Space (2000). “I feel that the head (brain) controls everything, the rest of the body only completes the idea of the head ”. Says Li Wei. “ When I do the Mirror series, viewers have the sense of the floating head in the air, without roots ”. The relationship between the head and body in Li’s works_ dramatize the complex tensions between reality and illusion in China’s today.

Li Wei began his career as a performance artist. Mostly his work his taken place in open public space-streets, markets, highway, square, for example. But sometimes his work has been presented on-site at exhibition venues, and occasionally in private space-houses, apartments, and courtyards. Most of his performances have been documented in photographs or video. For him the photograph is only the byproduct of the execution of his work. He pays more attention to the conception, the preparation, and realization of his works_.

At the outset of his career. Zhang Huan’s work inspired him a lot in helping to determine his own art. “I like the tension between human body and reality presented in Zhang Huan’s work. He is a brave man and strong-mind man, He has a strong sense of the Chinese people’s condition.” Says Li Wei. In the five years since he moved to Binghe residential compound where many artists have settled, he has learned how to realized his work accurately through working and talking with the artist Wang Qingsong. “My frequent and sincere communication with artists here, like Wang Qingsong and Zhu Ming, makes me understand more about contemporary art, and how to express perfectly my idea through performing and photographing.”

More important, Li’s oeuvre shows his insights into the psychological state of the Chinese people in this time of unprecedented social transition. His art is not stereotyped Chinese art, which has been highly appreciated by Western viewers, Li’s art is based on his own visceral experience of China, and it is articulated in the strong voice of his generation.

Although Li Wei feels that he owes a lot to many friends, including artists, photographer, curator, and partners, Li has indeed completed a large body of unique, creative work, which indicates his response to the changes in society. His art also shows an adventurous spirit in his efforts to interact actively within the new social context, and it is usually amusing, exciting, obsessive, ecstatic, and transcendental, suggesting a critical moment of an individual destiny. There is a theatricality throughout his entire repertoire. By viewing his works_, people can learn what is happening in China now, what young people are thinking about the world and themselves, and what the near future might be.